Solar magnetic activity

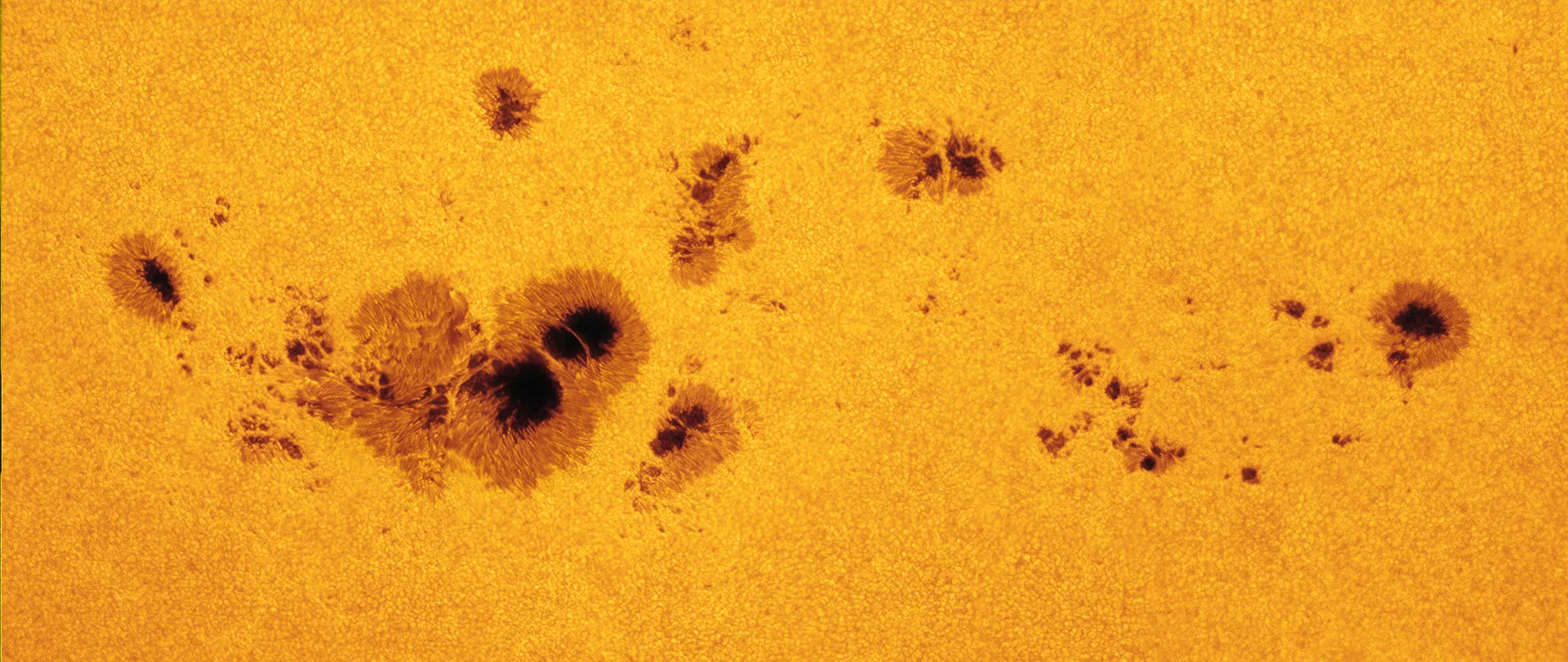

I am working on how the magnetic flux is generated in the solar interior (solar dynamo) and how it finds its way to the surface (flux emergence), as well as studying the Sun in the stellar context. Here are some results below (backward in time).

New papers (recently accepted):

- Krivova, N.A., Chatzistergos, T., Kazachenko. M., Işık, E. 2026, Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. A, arXiv preprint, Empirical flare energy limits for the largest historical sunspots

Quantifying sunspot group nesting by unsupervised machine learning (2025)

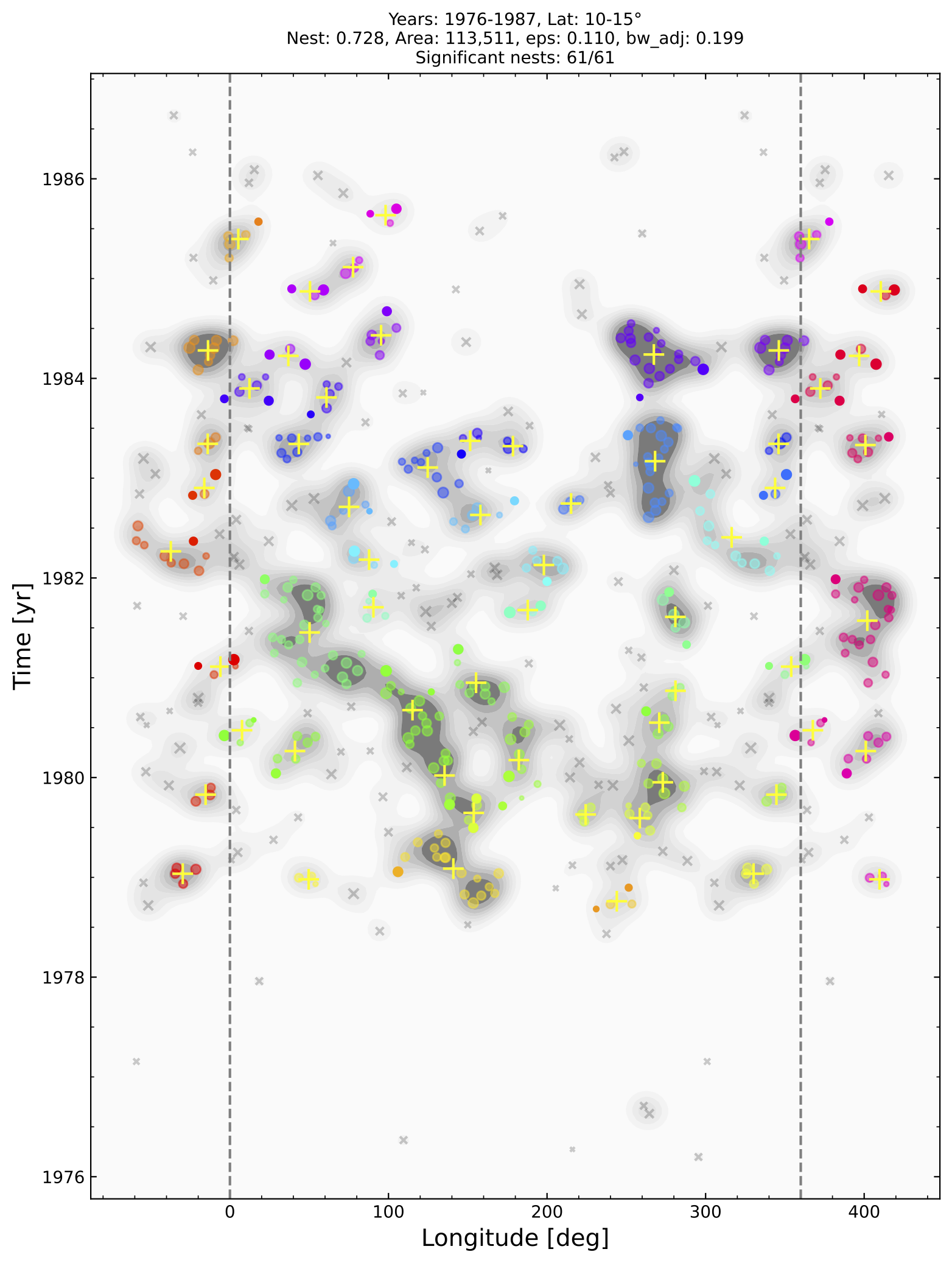

Emergence (first-observed) longitudes of sunspot groups between +10-15˚ latitudes through Solar Cycle 21. Coloured circles show members of nests centred at yellow crosses, the grey crosses show non-members (outlying groups). Grayscale contours show area-weighted density calculated by KDE with Gaussian kernel. The estimated nesting degree on this window is 72%

Sunspot groups do not emerge independently of each other. Instead, they cluster in space and time, forming structures called “nests” that persist for multiple solar rotations. Using machine learning techniques (kernel density estimation and DBSCAN clustering), we quantified this nesting behaviour across 151 years of sunspot observations from RGO (1874-1976) and KMAS (1955-2025) catalogues. This is a thesis work of my PhD student, Nurdan Karapınar at Ankara University.

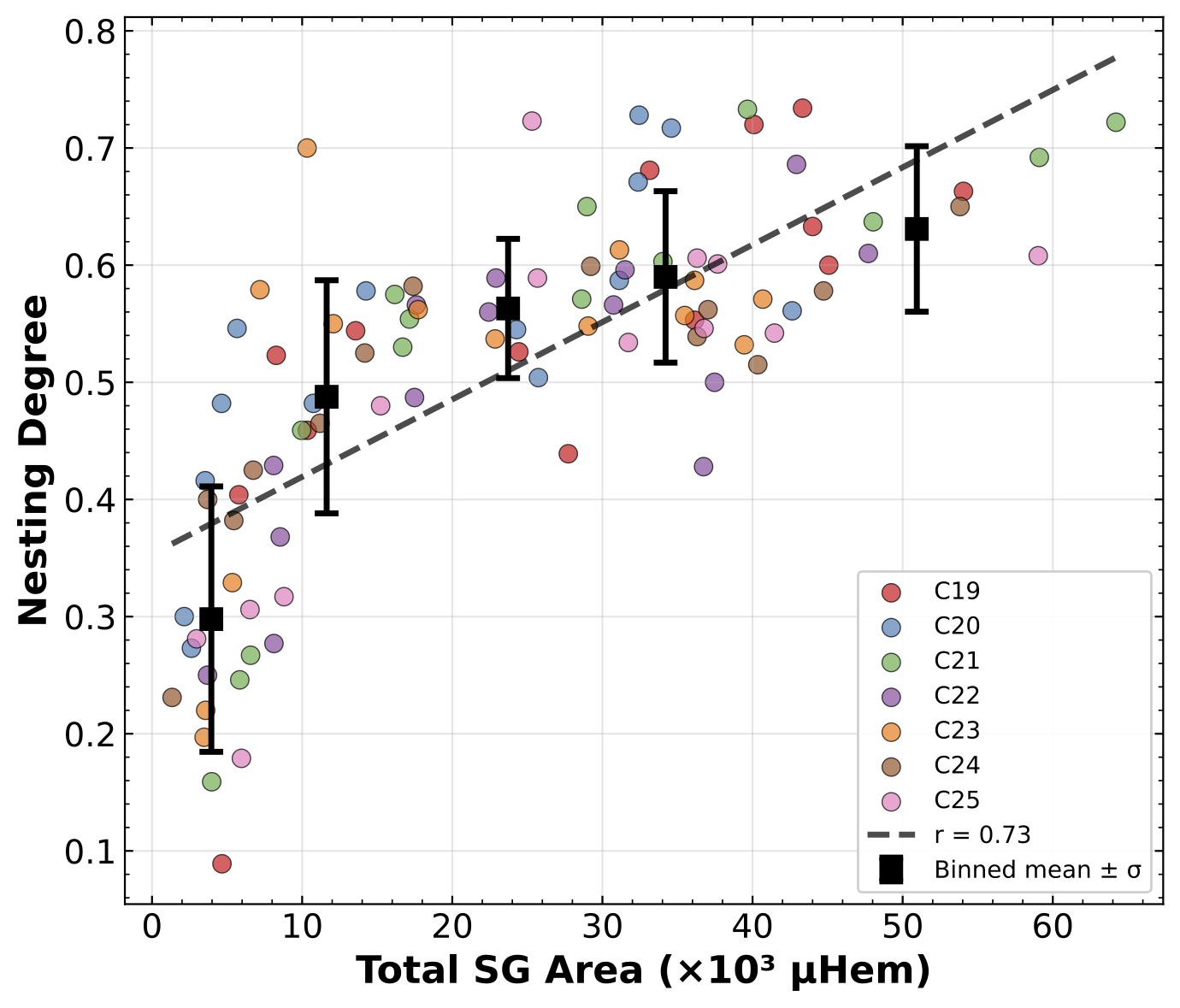

Nesting degree vs. solar activity level for KMAS datasets. Strong positive correlation demonstrates enhanced magnetic organisation during periods with stronger activity. Binned averages shown with error bars.

About 60% of all sunspot groups emerge within nests, with strongest nesting degrees at mid-latitudes (10-20°) where toroidal flux emergence peaks. The nesting degree correlates positively with solar cycle strength (see figure to the right). Critically, this correlation strengthens when small groups are excluded, proving it represents genuine spatial organisation rather than statistical artefacts from abundant small groups during active periods.

The analysis reveals hierarchical structure: small groups cluster strongly around large active regions (D≈0.55), while large groups themselves show reduced but persistent clustering (D≈0.25). Inter-nest spacing contracts from ~200-500 Mm at solar minimum to ~60-100 Mm at maximum, approaching typical sunspot dimensions. This quantitative framework provides new constraints on solar dynamo models and benchmarks for stellar activity studies.

Reference

Karapınar, N., Işık, E., Krivova, N.A., Şenavcı, H.V., Sol. Phys. 301, 34 (2026)

Plain-language and technical summaries (Gist.Science) — Disclaimer: Gist.Science content is AI-generated; refer to the original paper for accurate details.

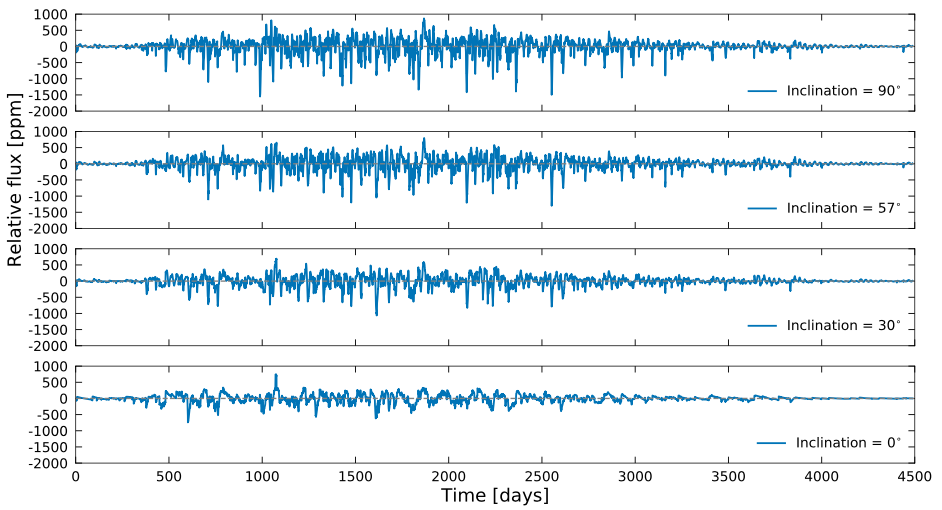

How would the Sun “as a star” look like if observed by Kepler or Gaia? (2020)

To better understand brightness variations of solar-type stars, it is instructive to view the Sun as a star. After all, we know in detail what is going on over its surface. In this study led by Nina Nèmec as part of her PhD thesis, we set up numerical simulations of the Sun’s brightness variations (its light curve), as seen from different perspectives with respect to its rotation axis, and through the sensitivity functions of space telescopes such as Kepler, Gaia, and TESS. It is generally assumed that solar brightness variations in Kepler and Gaia directly represent the solar irradiance variations (the total solar irradiance, TSI). Here we have shown quantitatively that this is a reasonable assumption. To conclude, we have shown that TSI is a good measure of solar variability, when considering the Sun among its stellar siblings. We also simulated (see the figure above) a decade-long light curve of the Sun for various inclinations of its rotation axis with respect to the line of sight, from 90˚ (Sun seen equator-on) to 0˚ (pole-on).

Reference

Nèmec, N.-E., Işık, E., Shapiro, A.I., Solanki, S.K., Krivova, N.A., Unruh, Y. 2020, Astron. & Astrophys. 638, A56

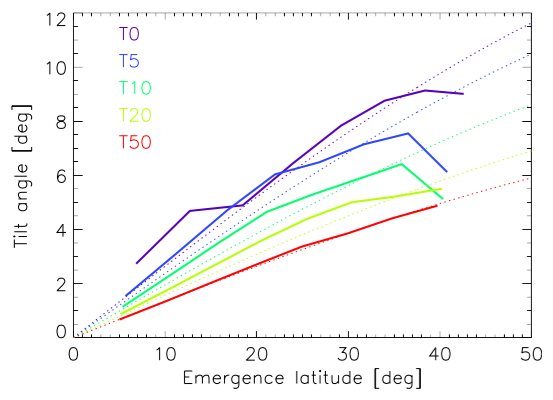

A mechanism for cyclic variations of sunspot group tilt angles (2015)

The average tilt angle of sunspot groups emerging throughout the solar cycle determines the net magnetic flux crossing the equator, which is correlated with the strength of the subsequent cycle. It has recently been discovered by Dasi-Espuig et al. (2010) that the cycle-averaged sunspot group tilt angle is inversely correlated with the cycle strength. I suggest that a deep-seated, non-local process can account for the observed cycle-dependent changes in the average tilt angle. Motivated by helioseismic observations indicating cycle-scale variations in the sound speed near the base of the convection zone, I determined the effect of a thermally perturbed overshoot region on the stability of flux tubes and on the tilt angles of emerging flux loops. I found that 5-20 K of temperature perturbation (cooling) near the base of the solar convection zone is sufficient for emerging flux loops to reproduce the reported amplitude of cycle-averaged tilt angle variations, suggesting that it is a plausible effect responsible for the nonlinearity of the solar activity cycle. The figure shows the tilt angle as a function of emergence latitude (so-called Joy’s law for sunspot group tilt angles) of toroidal flux tubes from numerical simulations carried out using thermally perturbed stratification models. In stronger cycles, the local cooling is enhanced, leading to a more stable stratification, which is responsible for stronger flux tubes becoming unstable, leading to lower tilt angles.

Reference

Işık, E. 2015, Astrophys. J. Lett., 813, L13

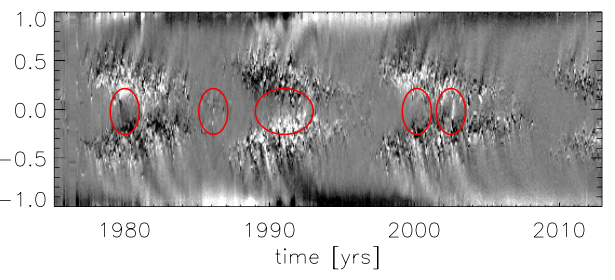

Limits to solar cycle predictability: cross-equatorial flux plumes (2013)

We have discovered (as a group led by R. Cameron from MPS) that near-equatorial emergence of BMRs (bipolar magnetic regions) with extraordinary properties can trigger unprecedented and substantial changes in the magnetic flux budget of each solar hemisphere. The impact can be quite strong if a large BMR emerges with a negative tilt angle, or when each polarity emerges at opposite hemispheres. Such events are quite rare and occur unpredictably. Our simple calculations demonstrate that local surface flows efficiently transport unsigned magnetic fluxes of the order of 10^{22} Mx poleward in some cases. Such flux plumes can lead to a reduction or enhancement of the polar fields that build up. Since flux transport dynamo calculations indicate that polar fields during an activity minimum are correlated with the toroidal fields of the subsequent cycle (see previous entry above), this means that the ‘next‘ cycle is highly dependent on Poisson statistics of rare events.

Reference

Cameron, R H, Dasi-Espuig, M, Jiang, J, Işık, E., Schmitt, D, Schüssler, M, 2013, Astron. & Astrophys. 557, A141

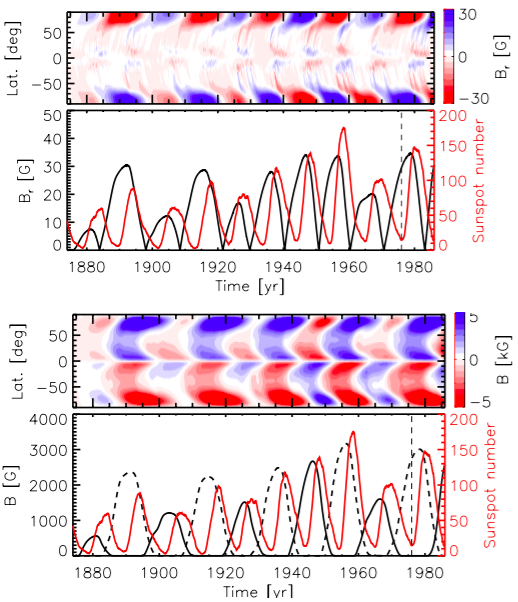

Modelling solar cycles 15-21 using a flux transport dynamo (2013)

Motivated by the results of the paper in 2012 (see below), we have run our flux transport dynamo model to simulate solar cycles for nearly a century. We have used the observed sunspot group areas and tilt angles to determine the average source magnetic field as a function of latitude at the surface. When the radial source field at the surface is fed by the observations, we have seen that the Babcock-Leighton-type dynamo model successfully reproduces the observed correlations between (a) the polar field at solar minima (second panel from top) and the strength of the subsequent cycle, and (b) the toroidal field near the base of the convection zone (bottom panel) and the strength of the subsequent cycle. The coloured time-latitude diagrams show the radial field strength at the surface (top) and the toroidal (azimuthal) field strength at the base of the convection zone.

Reference

Jiang, J, Cameron, R H, Schmitt, D, Işık, E. 2013, Astron. & Astrophys. 553, A128

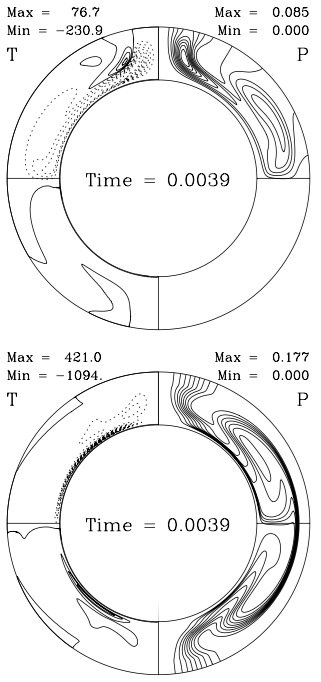

Constraining the flux transport dynamo by surface transport models (2012)

The surface flux transport model is currently the most successful tool in providing insights to the long-term variations in the solar magnetic field. The main reason is that it is well constrained by precise observations of the solar surface magnetic field in space and time. In collaboration with R. Cameron, D. Schmitt, and J. Jiang, we have used this surface model to constrain a flux transport dynamo model, which has more free parameters related to the deep interior of the Sun, where observations are much less precise and the MHD processes are poorly understood. We have found that downward magnetic pumping (turbulent and/or topological) should be considered in flux transport dynamos. Its role is to suppress radial diffusion of surface magnetic fields, so as to elucidate dynamo action in the Sun. The figure to the left shows the toroidal (T) and poloidal (P) flux densities for the case without pumping (top) and with pumping (bottom).

Reference

Cameron, R.H., Schmitt, D., Jiang, J., Işık, E. 2012, Astron. & Astrophys. 542, A127

The effect of activity-related meridional flow modulation on the solar polar magnetic field (2010)

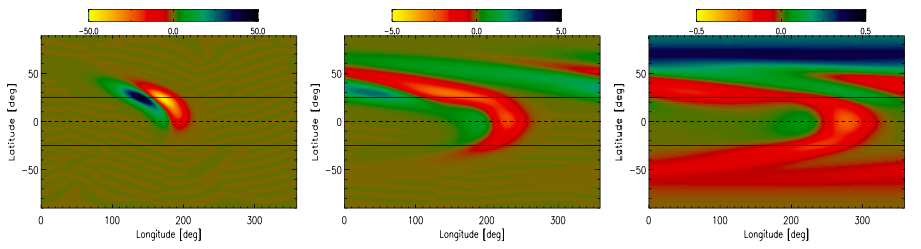

With Jie Jiang and the MPS Solar MHD group, we have studied the effect of cooling-related inflows around bipolar magnetic regions on the variation of solar polar magnetic field. The latter is an important ingredient in the flux transport mechanism thought to be responsible for the solar activity cycle. See for details. The figure (right) illustrates how a meridional flow perturbation affects the diffusive transport of a single bipolar magnetic region on the solar surface, which in turn determines the polar field. For stronger perturbations (stronger inflows), the effective tilt angle is reduced more severely, so that less flux crosses the equator, leading to a weaker contribution to the polar field.

Reference

Jiang, J, Işık, E., Cameron, R H, Schmitt, D, Schüssler, M, 2010, Astrophys. J., 717, 597

Flow instabilities in magnetic flux tubes: flux storage in the solar overshoot region (2009)

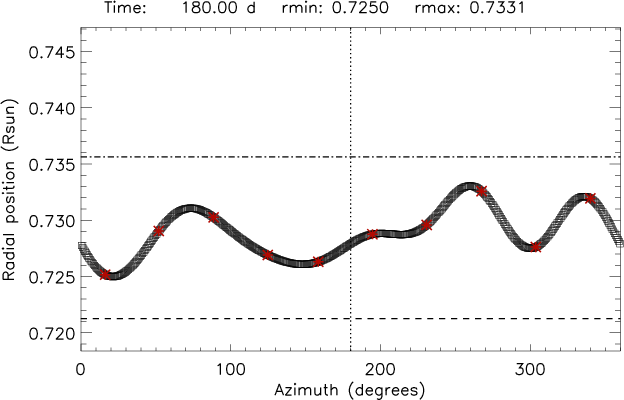

How significant are the effects of longitudinal and perpendicular flows on the equilibrium and dynamics of flux tubes, regarding the storage of magnetic flux in the solar interior? Investigation of this problem involves critical tests for the operation of a deep-seated dynamo in the Sun. In the figure, the shape of the flux tube is shown at 150 days after the beginning of the external downflow, centred at 180 degrees longitude. Click on the figure to see the animation.

Reference

Işık, E., Holzwarth, V H, 2009, Astron. & Astrophys., 508, 979